When Chen Cheng, a government official in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwest China, was appointed head of a village deep in the Taklimakan Desert, he had to take extra precautions for safety.

Baxlaqbinam, a struggling village in Pishan County in south Xinjiang, had seen some of its residents become radicalized. When Chen arrived there in the first half of 2017, during his visits to the villagers at their homes, he would go in a group with other officials as there had been cases where officials had been treated with hostility.

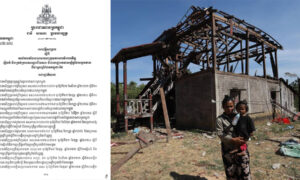

In 2017, there were 255 households in Baxlaqbinam. As one villager said, “Many of my neighbors didn’t have a decent house or electricity.” Many villagers had only temporary jobs, which fetched them a meager daily income only as long as the work lasted.

Pishan was like the proverbial person in distress caught between a rock and a hard place. Bound by the desert on one side and the Karakoram Mountain Range on the other, it struggled to feed its population of 300,000 as its arable land accounts for only about 0.1 percent of the entire area. Severe desertification made it impossible for the villagers to live off the land.

Since 2014, experienced officials began to be sent to the cluster of 169 villages in the county to improve their economic situation since poverty was a major factor spawning terrorism. Chen found poverty blocked access to education and made villagers vulnerable to the influence of radicalism.

More than 95 percent of the villagers are Uygurs, the largest ethnic group in Xinjiang. They knew little about what was happening outside their village.

One feasible solution was to provide education for the children and teach them Mandarin, the standard language of China, to help them communicate with people from other parts of the country and be informed.

Another solution was to create jobs by developing industries. In recent years, with Chen’s efforts, two factories have come to the village. One of them makes sofas.

The owner of the sofa factory, Xiong Tingqiang, came from Beijing. Earlier, he was growing dates in Pishan, and then he found that the traditional lifestyle promised a business opportunity. The villagers mostly sat on the floor or on their adobe bed, and Xiong realized sofas would have a good market if they were made locally and were affordable.

He started the business with Chen’s help. The factory provides jobs for 30 people and its sofas are sold in nearby towns.

Bumaryam Pazil is one of the factory hands. The 43-year-old makes slipcovers for the sofas, earning 1,500 yuan ($225) a month. Besides the income, the factory is some 200 meters away from home, which she finds most convenient.

“My husband has his job and I have mine. Everything is going pretty well now,” she said.

However, things were far from well four years ago, when she got married. Her husband Kudrat Ismayil used to sell timber. Though once well off, he ran into heavy debts when his first wife had breast cancer and his son from that marriage was diagnosed with leukemia.

Kudrat said he was always wary when he ventured out, worrying that he would run into his debtors. “I had no money to pay them back,” he told Beijing Review.

When Chen came to know of Kudrat’s plight, he helped him find doctors. The villagers’ committee also helped Kudrat and later Bumaryam to find seasonal work in other villages during the cotton-picking season and gradually, they were able to pay off their debts.

Now the villagers no longer need to worry about medical expenses, since a large proportion can be reimbursed under health insurance plans.

Kudrat has restarted his timber business. He also works as a ranger in the village wetland, which is being developed into a scenic spot as well as a nature reserve.

With the improvements, the village established a museum in 2018 to document the change in people’s lives. “The difficult life shown in the museum is a thing of the past,” Chen said when the museum was inaugurated. “The villagers are moving forward with hope for the future and lessons from the past.” Also, he no longer needs to move in a group. “Stability has brought a sense of personal security,” he said.

Women, family, future

Bumaryam started to wear make-up after she began working in the factory. “Women in the village never used mirrors before,” Chen said.

Nurgul, in charge of the women’s federation in Pishan, talked about the changes in women’s life after they started earning money.

“When we visited their houses and talked to them, most women were shy and didn’t look at us in the eyes when talking,” Nurgul said. “But as they now go out of their home to work and interact with more people, they are becoming more outgoing. At their workplaces they adopt new lifestyles from their colleagues who come from other places.”

Previously, when a married woman wanted to buy clothes, she had to ask her husband to buy it for her. Now she earns her own money and can buy it herself, Nurgul said.

Also, the tradition that the women would be the last to eat is also being discarded by young people, she added.

Nurgul was born in north Xinjiang, which has more oases and the lifestyle there is more modernized. She shares tips on health and how to tackle cultural differences with the village women, who seek advice from her when encountering a problem.

“Women are gaining respect at their workplaces and they are also learning from peers like Nurgul, who have received better education and are well informed,” Wang Jiangping, chief reporter of China Women News in Xinjiang, said.

“We encourage the men to share the housework and the male members in the villagers’ committee are willing to lead this new trend,” Chen said. “If they can’t take good care of their families, how can they serve other people well?”

The change is discernible in other counties as well. In the past, the women mostly stayed at home, looking after their families. People’s incomes were erratic and they were prone to poverty as the men had no work in winter, when farming came to a halt. But the new industrialized economy is helping them live a stable life full of hope.

More choices

For many families in south Xinjiang, farming is not the only way to make a living. Besides growing cash crops such as nuts and dates, locals work in factories and raise livestock as well. Their incomes have improved substantially thanks to the companies which start businesses there.

Tursunhan Tursunnyaz is a farmer in Luopu County, 200 km away from Pishan and at the center of Hotan Prefecture. She has recently become a full-time employee at the branch factory of dairy company Xiyuchun after a three-month internship. Her monthly salary has doubled to 2,500 yuan ($375).

“My husband had a donkey cart when I married him 15 years ago,” Tursunhan said. The couple grew corn and wheat, which brought them an annual income of around 10,000 yuan ($1,477). Though it was nearly double of what many other villagers earned, it was still a hard life for a family of four.

Liu Xiaojun, the manager of the factory, saw the market potential in Luopu, where half of Hotan’s population live. “There was no large breeding farm in Hotan,” Liu said.” Therefore, it was a big opportunity for us.”

The factory owns 1,100 cows which produce 11 tons of milk every day. Its dairy products are mainly sold in south Xinjiang.

“We have established a complete industrial chain and plan to sell dairy products such as yogurt and milk drinks,” Liu said.

The company provides 40 jobs, mostly feeding and milking the cows. In addition, it offers advanced breeding technology to villagers who raise cows. The county government invested 75 million yuan ($11 million) to buy cows for 3,766 households that were under the national poverty line.

Tursunhan has two cows. She plans to buy a car after selling her cows and has a driving license in anticipation.

“I have more money to spend now. I can buy clothes in the city [100 km away] and eat hotpot there,” the 34-year-old said. “I am going to continue working in the factory.”

Besides making extra money, she has changed her way of thinking. Unlike her mother’s generation, the mother of two said she is happy with two children, and wants to offer a higher standard of living for her family and invest more in her son and daughter’s education and health.

“I wish for my kids to go to college,” Tursunhan said.