Is it still worth investing in U.S. assets?

Following the U.S. president’s threat involving Greenland, calls to “sell America” continue to gain traction. Last week, the U.S. dollar index extended its downward trend, falling below the 98 mark. Bloomberg reported that mounting tensions between the U.S. and Europe have weighed on the dollar while reigniting global capital diversification. Inflows into emerging-market funds have surged at a record pace, pushing emerging-market equity indices to historic highs.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index has marked its fifth straight weekly gain—the longest winning streak since May last year. So far this year, the index has climbed roughly 7%, with Asian technology stocks as the primary driver of the rally.

“Confidence, once shaken, rarely returns quietly. If even a modest number follow-through — 2–3% of foreign holders — this could create massive ripple effects,” Financial analysis platform GoldSilver commented.

U.S. Dollar: no sign of a bottom

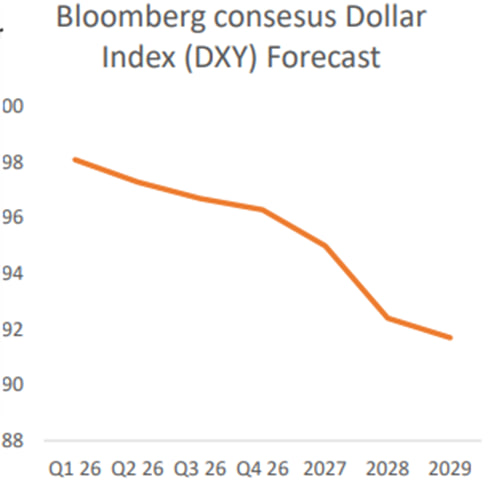

In 2025, the U.S. dollar index fell from around 108 at the beginning of the year to roughly 98 by year-end, a cumulative decline of 9.4% and its worst annual performance in eight years. Central banks, for the first time in decades, hold more reserves in gold than in U.S. Treasuries, signaling greater questioning around dollar hegemony and rising demand for geopolitical hedges.

According to a research report released by KTrade Securities on Monday, the slide reflects internal policy shifts and rising economic uncertainty:

- Fiscal Policy: Unpredictable tax debates and unfunded spending have shaken investor confidence.

- Tariff Uncertainty: Erratic tariff policies have made the dollar less reliable as a “safe-haven” asset.

- Institutional Trust: Concerns regarding the Federal Reserve’s independence and changing interest rate expectations have added downward pressure.

- Overvaluation: Years of a strong dollar reduced U.S. trade competitiveness. Current market shifts are correcting this overvaluation, though they are causing high volatility.

Dollar Index expected to trend lower in the following years. Graphics by KTrade Securities

Volatility in U.S. foreign policy have increased concerns for some countries about relying too heavily on the US dollar. Recent actions, including developments involving Venezuela, Iran and Greenland have encouraged reserve diversification and more defensive positioning.

This week, gold hit $5000/ounce mark for the first time in record.

“Dollar weakness linked to de-dollarisation is likely to unfold in waves. When geopolitical tensions rise or policy risks intensify, pressure on the dollar returns. When those risks subside, more traditional factors—such as interest rates, economic growth, and overall risk sentiment—tend to dominate,” Muhammad Faran Khan, Associate Director, KTrade Securities opined.

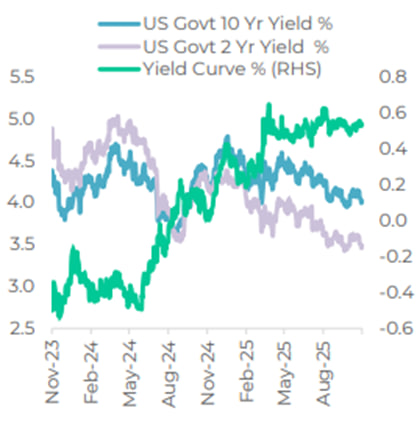

U.S. debt: no easy way out

Uncertainty prevails in the markets as investors are more focused on the U.S. fiscal outlook with expectations of a widening deficit seen as supportive for gold over the medium to long term.

U.S. national debt, heading towards an unprecedented $39 trillion, “has reached a critical parity with the total economy, with debt-to-GDP levels stabilizing near 120% post-2020, necessitating a structural shift in fiscal policy,” the KTrade report points out.

Long end of the US Treasury yield curve will face upward pressure, leading to a further steepening of the curve in 2026 as yields continue to rise. Graphics by KTrade Securities

Fundamentally, confidence on U.S. economic prosperity is weakening, eroding what underpins US Treasury attractiveness. Professional forecasters in the Blue Chip survey expect 1.9% GDP growth in 2026.

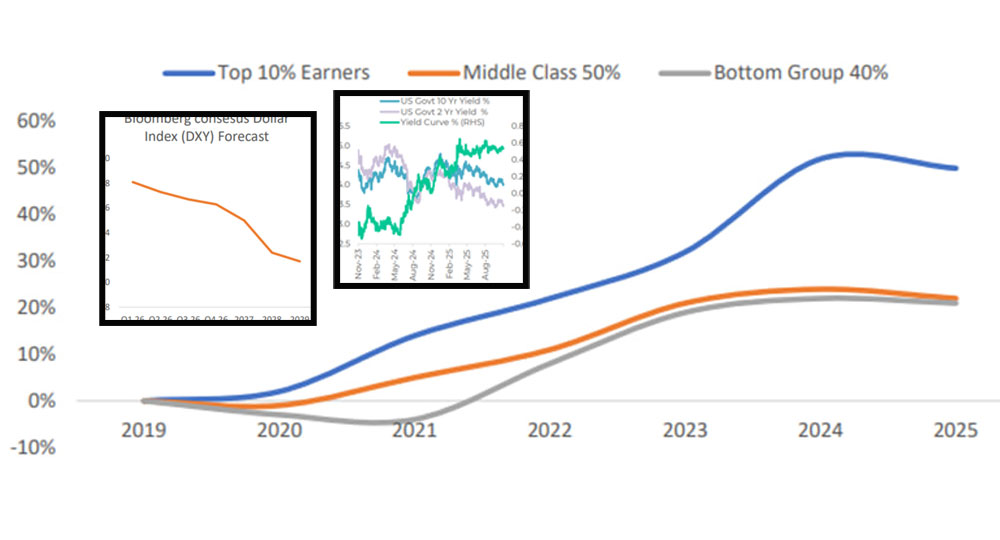

A stark gap persists between headline economic data and public sentiment. Last week, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) revised third-quarter 2025 GDP growth up to 4.4%, the fastest pace in two years. Yet growth figures inflated by gains among the wealthy and the AI investment boom offer an incomplete picture of the economy’s underlying health.

According to The Economist/YouGov poll, only 27% of respondents rate the economy as excellent or good, while 72% view it as fair or poor. Just 29% believe the administration’s policies have helped create jobs, as compared to 75% reported rise in prices. Sixty-one percent believe those policies have driven up health insurance premiums.

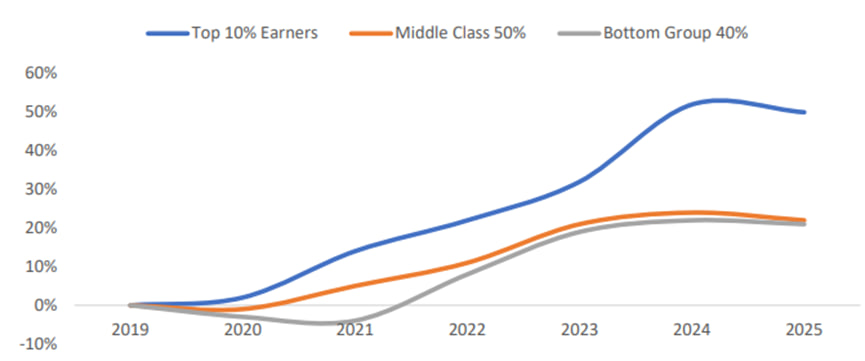

Studies found that behind the plausible economic figures, wealth divergence is stark. The top 10% of earners accounted for roughly half of all U.S. consumer spending—up from 36% three decades ago. These households, typically earning $250,000 annually, continued to benefit from rising asset values and strong business income. Their robust spending on luxury goods and services increasingly masked mounting financial pressures facing the rest of the population.

For the bottom 80% of households, spending growth barely kept pace with inflation. Many shifted from credit to debit, cut discretionary purchases, and attempted to rebuild savings. Credit card and auto loan delinquencies surpassed pre-pandemic levels. From Q4 2024 delinquencies increased significantly to record high levels. CNN recently reported, citing Bank of America data, that over the past year wage growth for middle-income households was just 2.3%, while low-income households saw gains of only 1.4%.

The share of U.S. consumption accounted for by the top 10% of earners has risen by nearly 50% since 2019. Graphics by KTrade Securities

A Bankrate survey found that 59% of respondents could not cover an unexpected $1,000 expense. PNC Bank’s 2025 report shows that about 67% of U.S. workers live paycheck to paycheck. The One Big Beautiful Bill is expected to widen income inequality, with plans to cut nearly $1 trillion from Medicaid, food assistance, and other social welfare programs over the next decade.

U.S. equity: not all that rosy

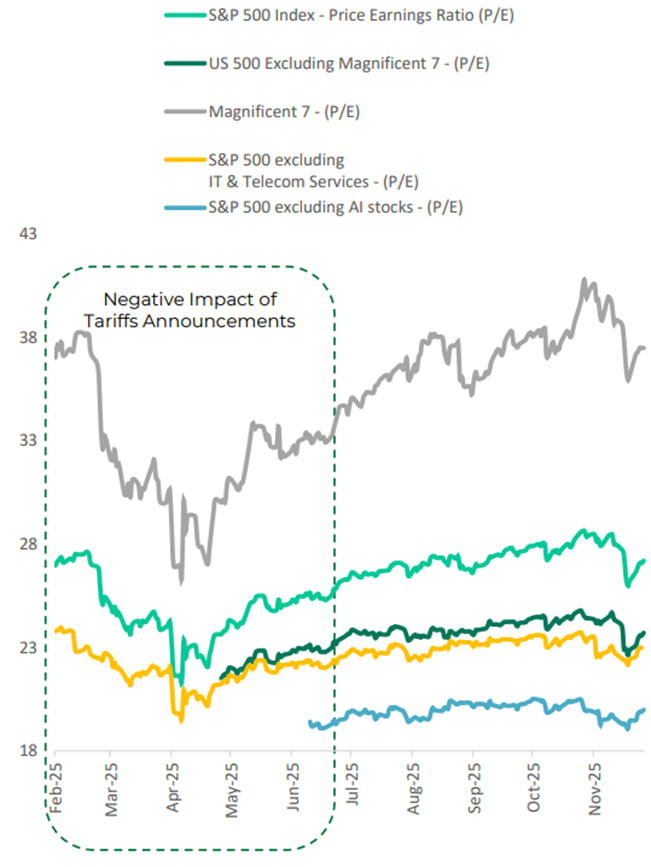

Overall, U.S. stocks added 16% on a price return basis in 2025, with gains majorly dominated by the “Magnificent 7” companies (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, and Tesla), which made up about one-third of the entire market’s value.

Given that only about 30% of S&P 500 revenues are generated overseas, undermined safe-haven status of U.S. assets due to declining dollar would weigh on corporate earnings.

Excessive concentration of U.S. stock market in the technology sector poses risks. Graphics by KTrade Securities So far, the stock market surge has failed to translate into broader wealth gains. Historically, the wealthiest 10% of households own around 93% of all individual stocks. As a result, the rally in the “Magnificent 7” technology stocks has functioned as a powerful wealth accelerator for those already holding substantial equity positions. As the S&P 500 approaches the 7,000 level, the bulk of capital appreciation has accrued to a narrow segment of the population, widening the participation gap in equity markets.

Employment data reveal deeper structural weaknesses in industries. The low-hire, low-fire dynamic has persisted, with firms reluctant to expand payrolls while still hesitant to lay off workers amid lingering post-pandemic labor shortages. Job growth has become heavily concentrated in healthcare. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the healthcare and social services sector added 695,000 jobs through November 2025, while total job growth across the economy stood at 610,000. In effect, without healthcare, the U.S. economy would have lost roughly 85,000 jobs.

Even the star sector—artificial intelligence—shows signs of froth. Major technology firms are projecting massive capital expenditure through 2030, with combined annual spending expected to exceed $500 billion, largely focused on AI infrastructure such as data centers and specialized chips.

Yet research from MIT points to a striking disconnect between AI investment and real-world outcomes: around 95% of AI initiatives fail to make the leap into production with measurable revenue or profit impact, with only 5% delivering tangible business results. Most failures are not due to shortcomings in the AI models themselves, but rather to brittle workflows and the inability to integrate AI effectively into day-to-day operations.

Muhammad Zamir Assadi